LIFE HARDER FOR CAMEROON GAYS

Life has become even harder for gays in Cameroon and death threats more common since a prominent gay rights campaigner was brutally killed a month ago, one of the country’s leading lawyers said.

Eric Ohena Lembembe, who had been fighting to legalise homosexuality in the central African country, was found by friends in his home in the capital Yaounde on July 15. His neck was broken, his feet smashed and his face burned with an iron, according to Human Rights Watch.

Alice Nkom, one of the few lawyers in Cameroon willing to represent men and women accused of homosexuality, said she and colleagues had voiced major concerns about the way the case was being handled.

“Sadly, the government’s reaction was defensive: ‘How can you tell that to the international press? You stain the image of Cameroon abroad’,” Nkom told Thomson Reuters Foundation in a telephone interview from Cameroon.

“But that wasn’t our intention, to stain anything. We simply wanted the police to gather evidence so that Eric’s death does not go unpunished.”

According to Lembembe’s friends, police officers who were called to the scene made no attempt to collect evidence or take photos before the body was taken to the morgue, Nkom said.

“As far as I know, no culprit has been arrested,” she added.

Nkom said that since Cameroon’s minister of communications rebuked activists for accusing the government of being lax in its response to the case, there has been an increase in threats sent to young men warning them that “you’re second on the list”.

“The situation has become worse (for gays). The authorities haven’t even issued a statement to condemn the crime. On the contrary, you now have young men who receive death threats on their mobile phones and are forced to behave as if they were in a thriller, and go into hiding,” Nkom said.

Lembembe, 33, was the most high-profile African gay rights activist to be killed since Uganda’s David Kato and South Africa’s Noxolo Nogwaza in 2011.

Washington, Paris and other world powers expressed concern over Lembembe’s death, in what is one of the harshest countries in Africa to be gay.

LOCKED UP FOR ‘LOOKING GAY’

Cameroon prosecutes people for homosexuality more aggressively than almost any other country in the world, activists say.

Nkom has said individuals must be caught in the act before they can be arrested or convicted, yet that has not stopped police from locking up people who are merely suspected of being gay.

Among Nkom’s large portfolio of clients is a man who was found guilty of homosexual conduct because he sent a text message to another man saying: “I’m very much in love with you”.

She also defended two men convicted of homosexuality in 2011 and jailed for five years for wearing make-up and cross-dressing. The convictions were later overturned by a court of appeal.

Human rights groups say arrests under article 347 of Cameroon’s penal code – which punishes “sexual relations between persons of the same sex” with up to five years in prison – have been on the rise since 2005.

Not only are individuals often held without charge for more than the maximum 48 hours allowed by law, detainees have also reported being beaten, forced to endure anal examinations by doctors and held in solitary confinement, according to Amnesty International.

TAKING DEBATE OUT OF THE CLOSET

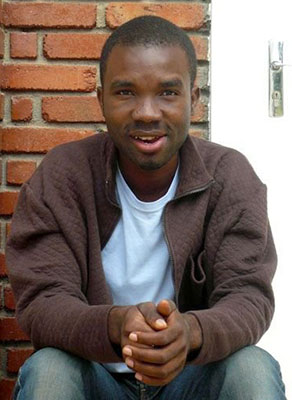

Alice Nkom

Despite Cameroon’s widespread hostility towards gays and threats to her safety, Nkom has fought for gay rights for a decade.

At the age of 23, she made history by becoming the first woman to be called to the bar in Cameroon. Now a 68-year-old grandmother, Nkom said she started defending Cameroonians accused of homosexuality after a meeting with a couple of young men who had come to her office.

“They were full of energy and sparkling with joy. I realised through their gestures that they were more than just friends,” she said.

Not only that, having lived openly as gay men in France, they had no idea about the persecution they faced in Cameroon.

“I did everything I could to bring the conversation towards the ban on same-sex conduct in most African countries, particularly in Cameroon. They were astonished. They couldn’t understand that this was possible,” Nkom said.

When she saw how their expressions darkened, she decided it was her duty to do something to help Cameroon’s LGBT (gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender) community, so in 2003 she created the Association for the Defence of Homosexuals.

“We can’t encourage our youth to study abroad where their sexuality and privacy will be respected … and then tell them ‘your place here is in prison’,” Nkom said. “That’s when I told myself, ‘we need a public debate and we must take it out of the closet’.”

Thomson Reuters Foundation News Service

Leave a Reply