Simon Nkoli’s fight for queer rights in South Africa is finally being celebrated – 24 years after he died

Born in 1957, Simon Tseko Nkoli had just turned 41 when he died, in 1998, of an AIDS-related illness. In his short life, the South African activist fought against different forms of oppression. He fought for those downtrodden because of their “race”. He stood up for those ostracised because of their HIV status. His greatest fight, though, was for those persecuted because of their sexual orientation.

Nkoli was born and raised in Soweto, the largest black township in a South Africa ruled by a white minority who enforced apartheid, a system of racial segregation. His activism began in 1980 when he joined the Congress of South African Students, a youth organisation fighting apartheid.

In 1984, Nkoli was arrested and became a trialist in the Delmas Treason Trial. During his imprisonment, he came out as gay to his comrades. This caused much debate in the liberation movement but it was important in changing the attitude of the African National Congress (ANC) to gay rights. The ANC would go on to govern the country with the advent of democracy in 1994, helping shape the first constitution in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation. Nkoli was responsible for setting up diverse projects including organising the first Pride march in Africa.

There has been a growing wave of interest in Nkoli’s life. South African musician Majola sings about queer love in isiXhosa, one of the country’s most widely spoken languages. His 2017 album Boet/Sissy has a song dedicated to the activist. Also noteworthy is the South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga’s sculptural work on Nkoli. A new South African musical production by composer Philip Miller called GLOW: The Life and Trials of Simon Nkoli is set to launch in 2023.

The annual Simon Nkoli Memorial Lecture is another event that celebrates the legacy of the late activist. The ninth edition was held in November 2022, co-organised by the Simon Nkoli Collective, where I gave the keynote address.

I argued that Nkoli’s activism highlighted the intersectionality of systems of oppression. Intersectionality refers to how multiple social struggles are interlinked. It recognises the interconnectedness of various systems of oppression such as racism, sexism and homophobia.

Nkoli was acutely aware of how these were interrelated and this article considers what can be learnt from his activism today.

Intersectional systems of oppression

In a compelling speech in 1990 before the first Pride march in Johannesburg, organised by the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW), Nkoli said:

This is what I say to my comrades in the struggle when they ask me why I waste time fighting for moffies (a deregatory Afrikaans language term that means faggot). This is what I say to gay men and lesbians who ask me why I spend so much time struggling against apartheid when I should be fighting for gay rights. I am black and I am gay. I cannot separate the two parts into secondary and primary struggles. In South Africa I am oppressed because I am a black man, and I am oppressed because I am gay. So, when I fight for my freedom, I must fight against both oppressors.

Nkoli recognised that the struggles of queer folk are linked to the struggles of women and that the struggles of queer folk and women cannot be disconnected from those of black people.

He was, however, aware of the fact that the intersectionality of struggles had its limits. Although queer people of different classes and races marched together in 1990, he was not so shortsighted that he believed all those people were considered equal. He explained in a 1989 interview that even within the queer liberation movement there were splinters due mainly to racial differences.

Nkoli’s activism ensured that the rights of sexual minorities were enshrined in the Bill of Rights of South Africa’s constitution of 1994. This was done through the advocacy work of organisations like the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality that brought together diverse organisations.

What we can learn from Nkoli today?

We learn from Simon Nkoli that the fight for social justice and social equality demands collaborative and joint efforts. I muse at the isiZulu language term for intersectionality coined by a student activist, Zandile Manzini: “ukuhlangana kobuntu”. Any sustainable forms of fighting against social inequality are built on the idea of returning the humanness to people. Fighting oppression demands that the humanity and the dignity of everyone is respected regardless of social class, race, ethnicity, political affiliation, sexual orientation, gender identity or nationality.

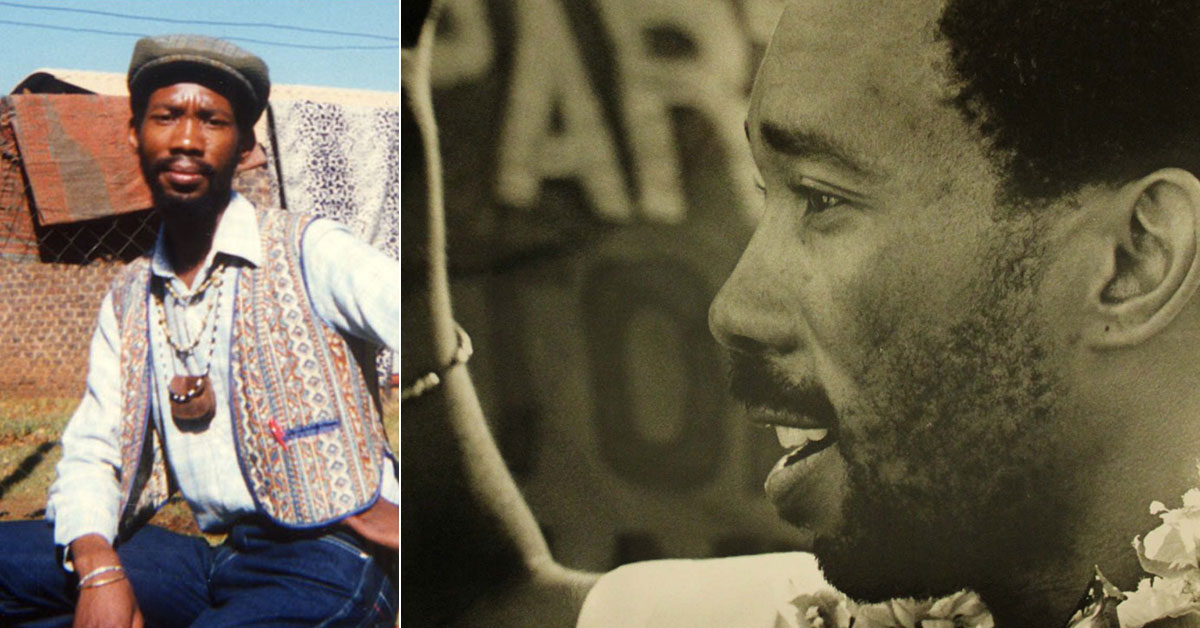

Simon and fellow activist Phumi Mtetwa with Nelson Mandela and actor Ian McKellen (Courtesy the National Coalition for Gay & Lesbian Equality Collection/GALA Queer Archive)

Retired South African judge Edwin Cameron, himself openly gay and living with HIV, explained Nkoli’s legacy at the opening of the Simon Nkoli exhibition at the Stellenbosch University Museum in 2019. He said that Nkoli’s activism crossed boundaries and had resonated in many other parts of the continent.

As artists and activists commemorate and celebrate the life and legacy of Nkoli, let us remember his fight for the creation of a democratic South Africa in which all people could live dignified lives without fear of discrimination. As we remember Nkoli, we should think through what other fights still need to be fought, what systems of oppression still need to be unbuckled and what solidarities still need to be forged.

Article by Gibson Ncube, Lecturer, Stellenbosch University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Leave a Reply